“Faces and Phases at Prospect Park Deli”

by

Maya Kingstone Frei

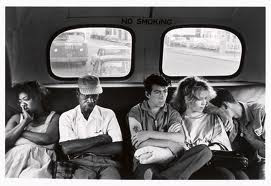

I am three years old. I have just moved from Toronto to Windsor Terrace, a small neighborhood of Brooklyn that lies between the Tudor Revival architecture of the residential Ditmas Park and the bustling commerce of bourgeois coffee shops in Park Slope. I live in a red-bricked building on Seeley Street, six stories high, ninety years old, and crumbling as fast as it’s fixed. Around the block, in between the laundromat and the pizza place, lies Prospect Park Deli. With “PROSPECT PARK DELI'” stamped in big, white capitals across a scarlett awning and brightly-colored advertisements covering every inch of the storefront, a big neon sign sits on the street in front, flashing the kitchen menu ($2 Coffee and $5 bacon egg and cheese sandwiches are just about all you can get). Next to the door, which sings a funny little jingle each time it opens (think entrance music as a circus clown arrives on a unicycle, or something you’d hear in a cutesy children’s show theme song), there is a small window looking from behind the counter onto the street, greasy with fingerprints and always opened. Nick, the owner of the deli, is a 50-year-old Palestinian man with a bushy beard and a hoarse, gruff voice from decades of smoking cigars. He has folding chairs and wooden benches outside for the faces that live at the deli. At three years old, I did not know why they were there all the time, but I would watch Nick pass them cigarettes, sliding off of his stool and leaning through the window. Jacob, my elderly neighbor, with thick, gray dreadlocks and a snickering laugh, sits outside the deli often. He always smiles at me from the folding chair, cracked, brown teeth and beady eyes, but there is a warmth there. My parents don’t like it when I talk to him. I don’t know why; he seems nice. After a long day at Prospect Park in the playground across the street, I go to the deli for a strawberry popsicle or a 50-cent bag of cool ranch Doritos. Nick has a family: a brother that works in the morning, who moved to Brooklyn from Palestine with Nick twenty-something years ago, and two sons. One of them, Ahmed, is around my age, one year younger. While my parents pay for my treat, the two of us play with the kitten that lives at the deli, a black and white cat named Lotto, young but fat and lazy with missing fur and crusty eyes. I am three years old. I know nothing about the world.

I am nine years old. I have started walking to and from my elementary school, a short distance from my building past the deli and down 10 blocks to Church Avenue; my first taste of independence. Every day after school, I stop in at Prospect Park Deli for a snack before I get home. I always see Ahmed; we aren’t friends but we always wave hi. I watch him, eight years old, sweeping the floor and stocking the shelves, balancing on tiptoe on a stepstool to reach the higher ones. I have never worked a day in my life and I feel sorry for him. I am also jealous of him, in a way. He makes me feel young and naive, like he knows more about the world than I do; he knows struggle more than I do. Lotto the deli cat is still there, older and fatter. He is always sleeping on the dirty floor of the deli, under a shelf of cake mixes and frosting. Jacob is still there, too. Without my parents to pull me away, I get to know the faces of the deli a little better. Maria, a small old woman with no teeth and a thick accent. I know she is Hispanic but I can’t quite place where her accent is from, partially because she has no teeth, which makes it difficult to really hear her. She is sweet and always smiling, taking my hand and telling me she wishes she was young and pretty like me. I think she is pretty. Will, a thirty-something year old with a buzzcut who lives around the corner and always wears gym shorts and a blue baseball cap. He smokes a joint, long and pungent with thick, light yellow smoke curling around him, and tells me about his times skiing in Colorado. I am nine years old and feel silly next to these people; they tell me stories and they seem to have lived and I don’t think I have quite yet.

I am thirteen years old. I am nervously approaching Nick with a case of White Claws in my hand, taken from the fridge in the back. I have never drank alcohol before but my friends and I agreed it was time; we are thirteen and think we are all grown up. I give Lotto a scratch behind the ear and drop the case on the counter with a heavy thud. Jacob sees me through the window. He went through tough times recently. He had three cats, who he would play with in the outside corridor between the basement and the garage of our building. They all died this year. My mom, then president of the co-op board of my building, told me that Jacob had got in some trouble. His apartment was dirty, smelly, and unkept, so bad that I saw men in hazmat suits come in with sorts of cleaning supplies I had never seen before. The building wanted to evict Jacob, but my mom fought for him. She explained to me that if Jacob was evicted, he would have nowhere else to go. I didn’t quite understand the gravity; I wasn’t as grown up as I thought I was. But it seemed unfair to me. Jacob had lived in the building for 60 years, longer than anyone. He had every right to live there, but all the rich millennial parents of toddlers that had just moved in (housing prices in the neighborhood had doubled in the last five years) didn’t think so. My mom won the fight; he didn’t have to leave. I watch Jacob from the corner of my eye as I smile at Nick. He looks at the drinks and laughs, shaking his head, “You’re all grown up, I see”. This makes me laugh, too. He sells me the case. Later that night, I am sick to my stomach and vomiting into a park trash can. I feel stupid, like a little kid.

I am fifteen years old. There is a new face at the deli: Rosie, an eighteen year old who has recently been kicked out of her parent’s house. She moves from couch to couch, but really lives at the deli. When she is not working on her true passion, videography, she is a bottle girl at a sketchy club in Bushwick. She asks me if I want to work there too. I am old enough to know I don’t have to, not like Rosie does. She suffers in a way I don’t. I have just been fired from my first job, cashiering at the KeyFoods three blocks from the deli. I am walking home crying; I feel immature and foolish, a failure. I find myself at Prospect Park Deli. Nick sees me crying through the window. I tell him what happened and he pities me and gives me a twinkie. He tells me to go to the garden in the back to collect myself before the walk home. As I step through the back door, I wrinkle my nose at the smell, unplaceable but certainly unpleasant. Jacob, Maria, Will, and Rosie are sitting around a folding table under a green, wooden shed with a few other middle aged men I don’t recognize. I tell them what happened and they pity me; they say they will never go to KeyFoods again and they feel comforting, a community. Jacob asks me if I am okay with them smoking. I say sure; I think nothing of it. As Jacob pulls out a crack pipe, Rosie whispers to me that I should leave and I think that I am not as ready for the world as I thought I was.

I am seventeen years old. On the way to the subway before school, I always stop at Prospect Park Deli. I grab a 99-cent Arizona iced tea and sit for a while outside the deli, below the little window on a stool. Jacob gives me a cigarette, lifts my chin to light it, and we talk about Buddhism and literature. I am old enough to know why Maria has no teeth, old enough to know that Will has never been to Colorado, old enough to know why the young parents don’t like Jacob smoking crack in the building their children live in. Ahmed, now sixteen, still works at the deli. My old playmate sells me alcohol and we talk about the Middle Eastern conflict and what we want to do with our lives. His older brother is there less now. He is getting a degree at Hunter College, where my dad works. My parents no longer go to Prospect Park Deli; they don’t like Nick or Jacob anymore, don’t like me being around them.

I talk to the faces at the deli about my plans for college. This shocks me into the heartbreaking realization that, as I am leaving Brooklyn, the community I have found at the deli is not one I can ever return to. There’s no way to know what could happen in the next four years, if the faces at the deli would still be there, or still be doing okay. This community is fragile: balanced precariously on deep tragedy and beautiful solidarity. I didn’t truly reflect on the significance of the deli to me until it was just about over. Even if I move back to Brooklyn after I graduate college, and the faces of the deli are still doing okay, I wouldn’t belong there anymore. I will no longer be a child, invigorated by sweets and stories. I will no longer be in middle school and grasping wildly for a taste of independence. I will no longer be a teenager, drinking white claws and thrilled to sit on a street corner with Jacob and smoke a cigarette. I will be a young adult. I will be educated and pursuing a future that I am privileged enough to have access to. I won’t have a place at the deli. It makes me sad. It makes me long for the simple days of childhood. It makes me angry at the world for giving good people shitty lives when they deserve better. It makes me uncomfortable, too; a brutal awareness of how lucky I am, and how unlucky others are. I won’t talk to the deli faces about it; they don’t need me to tell them that they suffer. Instead, they like hearing about my life, how it’s all ahead of me; their lives are far behind them. I don’t think they really even live anymore.

No comments:

Post a Comment