“Sunset Park, 1950s”

by

Karen Heuler

The first home I remember was an apartment on 45th Street between 4th and 5th avenues in the Sunset Park section of Brooklyn. The apartment itself is hazy, but the view from the street looking down the slope to the bay appears still in my dreams. It’s flat, like a Grandma Moses painting, so the water really appears to be a wall. It’s like wallpaper on a computer screen, though, in that the image is always waiting for me to return.

Back then, if you weren’t in school, you were on the street playing with all the other kids. Johnny on the pony, stickball, stoopball, any kind of game. You jumped copings and every so often someone would fall and break their collar bones, as my younger brother did. You wouldn’t tell your mom right away because moms made arbitrary rules like not ever doing it again. There was a definite border between the things we told each other and the things we told our parents. But when a woman took my younger sister by hand and dragged her around the corner, the kids followed and yelled and someone got an adult and so the kids protected each other as often as they insulted and jeered at each other. Maybe more. We kids were a community.

If I walked that flat image of the street looking down to the bay, I would get to the trolley tracks down near the water. By the time I was seven, the trolleys had stopped, victim of cars and Robert Moses and cutthroat competition. But that area had a certain spooky charm, mostly abandoned, cobblestoned, away from the civilization of 45th St. You had to cross the tracks to get to the fish and chips place with its fried foods on newspaper. It was a viable business for a while, and a welcome relief from fish fingers, which we got far too often because my mother was Catholic and my father had married in. Catholics didn’t eat meat on Fridays then. My sister and I were sent to Catholic school; my brothers went to public school. I think this was to make sure the girls didn’t stray, but also because it was cost too much to send all four of us. Corporal punishment was still allowed in school, and the nuns believed in it. Most people believed in it. I remember my parents were late paying tuition once, and all the kids whose parents hadn’t paid were stood in front of the classroom, hands out, and they got their hands smacked with two rulers that were rubber-banded together. Another time, someone tossed an empty chocolate milk container in the courtyard and the PA announced that everyone in the school would be spanked until the culprit confessed. About 5 minutes in—the spankings were in progress—the PA came on again and said the culprit had been found.

I hated that school, and the Catholic high school I had to attend later on, after we moved to Bensonhurst. But as a child, the natural gangs of children and their interests made life wonderful. Kids were always finding new things, devising them, using them, moving on from them. There were waves of interests, some of them unpleasant. The boys made and used zipguns using cut pieces of linoleum for a while. Something must have happened because suddenly there were no zipguns on the street. Instead, the neighborhood (or my block at least, which was a neighborhood) leapt into making go-karts. These were all manual, all made from homely articles—very often roller skates or the bottoms of baby carriages or bright red wagons—and designed for reckless speeds (probably 5-10 miles an hour downhill; they didn’t go uphill).

Half of the joy in go-karts was in designing them. I can remember sketching out a go-kart using roller skates united by a plank of wood, with an orange crate facing inward in the front, where you stuck your feet. My plans contained a steering device, usually rope tied to the wheels. I think there was a chair or part of a chair nailed to the back end, and some way of making a rain cover. As I got more sophisticated, I swapped out the skates and used baby carriage wheels, and the braking system was a stick of wood. My plans had lots of arrows and explanations because those were a sign of real engineering.

I never made that go-kart. I didn’t have the materials and after a year or two we all outgrew them and moved on to something else. But the planning was glorious and it fed a community that was focused intently on creating an object both useful and aspirational. The odd part was that it remained imaginary. Boards on skates just weren’t true go-karts, which required more creativity. We were testing the world and our place in it, and each new game moved us onwards, much more so than did the game of doctor carried out in vestibules in our buildings, games that were often discovered and broken up by adults, and which didn’t—at that age—hold more than an educational appeal.

On Saturdays our parents would give us each a couple of quarters, which paid for a double feature movie and a bag of popcorn. The movie theatre was filled with kids for the cartoons and whatever the features were. It didn’t matter. A theatre full of kids isn’t really paying attention to the screen. It was 15 cents for the subway, and 15 cents for a slice of pizza, and for a while the two of them kept pace with each other. That price of course seems crazy, but cars cost a few thousand dollars, gas was .33 a gallon, and no one made much money. My father worked in a steel factory in New Jersey. One friend who worked there picked him and dropped him off each day. He had never finished high school and the job didn’t pay very well. He got up around 6:30 am, got us up, fed us breakfast, and left soon after, getting home around 7pm at night. He worked days and my mother worked nights. The six of us lived in a 5-room apartment. My sister and I slept in the dining room. But outside was the street, alive with kids and noise and running around. There was a park about four blocks away, and to get to it we had to pass the candy store, with glass counters featuring buttons on a strip, waxy little bottles filled with colored sugar water; candy watermelon slices, orange slices, jawbreakers, edible lipsticks or mustaches or cigarettes; mary janes, pixy stix, satellite wafers, candy necklaces, candies that we bought because the shape was fun even though they weren’t tasty. In the summer they sold slices of watermelon that we could grab for 5 cents on our way back home. My father salted watermelon and put sugar on oranges; we didn’t.

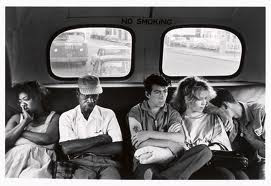

The street children were every age until teenage; then these drifted off into their own group, playing rougher. Stickball got malicious; there were fights. I don’t think any of the fights were serious, though. But teenage lives were hidden from us; they went elsewhere while we played skip rope.

We moved when I was eight, from Sunset Park to Bensonhurst, which was a strange country to me. Street life didn’t seem to exist in Bensonhurst. There were no street games. Maybe those existed in the side streets, but we lived on an avenue. Neighborhoods in New York City are boundaries; enclaves; towns; You stuck to your place, and a totally different life could be invisible a block away. There was a girl next door, but she was an indoorsy kind of girl. And there were different divisions of schools—Catholic, public, perhaps even Jewish because I could occasionally hear the shofar call two blocks away. But we didn’t mix. Kids stayed home until they got old enough to drive a car and then they double-parked or honked at each other and drove to deserted areas to drag race. I don’t know what in particular makes one neighborhood fun and the other stuffy. I do think we moved from working class to lower middle class, but how did that change the children? I think of how protected children are these days and. How wonderful it was to be on the street and running rogue. I imagine working class kids have a lot more freedom than middle class kids, who watched too closely. I may be wrong. I know that boredom was common after we moved to Bensonhurst. I read a lot; I always read a lot. But I missed the shouts, the spins, the games, the exuberance of children unleashed on the streets. I have images of kids shouting in groups, all together, eyes on each other. Sure, pushing and shouting at each other and having fights, but always running out, each day, to find their neighbors and friends. And behind them, down the street but somehow rising up, the bay.

No comments:

Post a Comment