“Sometimes I Forget”

by

Jim Loughead

I lay under my bed, hiding, listening as my father made his way from the living room to the bedroom to punish me. Why? I have no idea; I was five years old and had committed some egregious offense punishable by whipping with his belt, his black leather belt. The belt, folded in half and then pushed open, formed a closed circle and made a sharp slapping sound when pulled together. His slow, deliberate steps prolonged the anticipation of my punishment. My legs trembled, and my heart pounded as I listened to the belt slap as he approached the bedroom. The dark stain in my shorts, only a matter of minutes away, was another egregious offense. I watched his black polished shoes enter the room, stopping as he scanned the room to determine my location under the bed. As he moved, I moved, holding my breath, sliding on my belly through the dust balls in slow motion to keep my distance, delaying the inevitable. Like a frog catching flies, his patience and persistence paid off, and once he seized my ankle and dragged me out, my fate, like the fly’s, was sealed.

My parents, two younger sisters, Lynn and Maggie, and I lived on Lynch Street, Brooklyn, in the ground-floor apartment of a beautiful brownstone house. A large shady tree stood in the front yard, providing relief during the sweltering, humid summer months and a playground with falling leaves in the Fall. The stoop rose from the sidewalk, bordered on each edge with a black wrought iron handrail, up to a looming double glass door whose beauty I can appreciate now but did not then.

The landlords of our building, Mr. & Mrs. Rosario, lived on the second floor in an apartment like ours. The Rosarios were a friendly and loving Italian couple with a "straight off the boat Italian accent" who treated our family like theirs. They were always smiling, tugging on our cheeks, and Mrs. Rosario gave the warmest bear hugs; they were our surrogate grandparents.

Mrs. Rosario treated my mother like her daughter, and my mother loved her. On the weekends, the extended Rosario clan showed up at the apartment to eat, drink, and be a family. When Mrs. Rosario began to prepare the food for the weekend, the smell of Italian cooking and garlic wafted throughout the building. Sooner or later, there would be a couple of thumps on our ceiling, signaling us kids to go upstairs to her apartment for some bread and red meat sauce. Sometimes, she brought down a platter of spaghetti and meatballs for our family supper. When Maggie heard the thumps, she jumped up and down joyfully, shouting, "Begetti! Begetti!" A classic example of Pavlov’s Classic conditioning theory at its best! After Mass, the Rosario family arrived mid-morning Sunday, dressed in their "Sunday best." The men smelled of cheap aftershave, and the heavy use of Brylcreem kept their hair waxed down and in place. The younger ladies wore brightly colored dresses with bright red lipstick and cheap perfume, and the older generation wore black dresses and head scarves.

On warm summer afternoons, the party spilled onto the stoop and front yard, where the adults sat around smoking cigarettes and drinking wine until late at night. The adults were boisterous, animated, and always laughing, deep infectious belly laughs. Their native tongue echoed up and down the brownstone’s dark cavernous hallways and stairs due to the constant motion of kids and adults between the apartment, stoop, and street. While the adults entertained themselves, the kids went onto the road for a stickball game with other local kids. At age four or five, I joined the kids on the street in these games and one of my happiest memories involved playing one of these stickball games. The sun shone bright, and the heat and humidity lay like a wet blanket over the players but did not dampen anyone’s enthusiasm. Kids fielded the bases and played the outfield between the parked cars. My dad and Uncle Mike stood on the sidewalk, shouting words of encouragement as I approached the plate. I swung and hit a line drive, shooting it down the street and passed the outfielders. As I headed home, I charged around the bases, my skinny little legs pumping like tiny pistons. I slid into home safely and into the arms of my yelling father, who scooped me up and tossed me into the air, screaming, "Home run! Home run!" Happiness oozed from my pores as my dad passed me off, shouting to Uncle Mike, " he did it, he did it." At that moment, I became an innocent, happy kid again, enjoying life and forgetting about the belt and the booze. Uncle Mike carried me over to the stoop, where the Rosario clan passed me around for a round of head patting, cheek tugging, and wet kisses. Somewhere among the celebrations, someone slipped a nickel into my tiny hand. I was rich, the richest I had ever been in my young life! What a day!

After many of our games, our small, dusty, sweaty bodies were treated to a street shower, an open fire hydrant, or "johnny pump," as we called it. We jumped, dashed, and played in the cool, refreshing water, many of us bare-chested and in our fashionable “tighty whities.” The Italian kids showed off their olive-skinned Mediterranean "brown body looks," a sharp contrast to the vanilla white, bony, red-armed Irish kids who resembled animated Christmas candy canes. Dozens of kids shrieked in delight as they danced through the ice-cold spray and puddles until the cry went up: "Police!” or “Fire Department!” Like a disturbed hornet’s nest, half-naked kids darted in all directions back to the safety of their stoops and vigilant parents. We watched dejectedly as the firefighters closed the pump and listened to the good-natured banter between the parents and the firefighters. A chorus of boos started when we realized the firefighters were closer to their trucks than to us!

On the weekends, my parents frequented a bar on Marcy Avenue run by an Italian man named Cuz. A red Rheingold Beer sign hung behind the bar where the men drank beer, smoked, and argued about who was the best center fielder in New York. Willie? The Mick? Or the neighborhood favorite, The Duke? The mothers herded the kids into the back room and, along with my cousins and the other kids from the neighborhood, fed and entertained us until it was time to go home. The singing started as the afternoon progressed towards the evening, and the drinks flowed. A soloist would burst into song from their “old country,” an Irish ballad of freedom, or a song in Italian, words I did not understand but knew, even at that young age, sung from the heart. Before the night ended, the neighborhood became one in a singalong as these immigrants, the heart and soul of Brooklyn, our country, and part of the Greatest Generation, remembered the "Old Country.” Two communities from distant shores, united in song, under one roof in Brooklyn, a true definition of the melting pot of America. It felt like magic. On these nights, I stood mesmerized, watching the singers, and discovered my love for music. As I write this, I wonder if the musical greats from Brooklyn, Streisand, J Zay, Manilow, and Neal Diamond were as lucky as I was to experience similar nights.

The occasional weekend visit to the bar soon became every night for my dad. He started coming home from work late at night, "walking funny," and instead of singing, he mumbled. When he did arrive home, my mom put us to bed, and the fighting started. We listened as the arguments got louder and the occasional plate smashed on the kitchen floor, or a pot clanged against a wall. Screams and fights replaced the laughter and the songs from the “old country.” The nights of laughter on the stoop, the happiness of stickball, the treats of Mr. Softee ice cream, and the peanut man all disappeared into the darkness of the bottle.

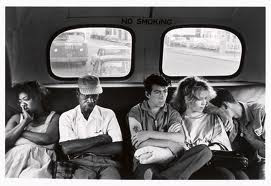

Other memories from my “Brooklyn Collage” involve some good times of those early days. As she put us to bed one evening, my mom told us that tomorrow would be special because we were going on a trip. It was hard for me not to contain my excitement, so when I woke up the following morning, I bounded out of bed and into the kitchen, where both my parents were. My mom stood by the kitchen sink, the filtered sunlight highlighting her smile and colored floral dress. My dad sat at the table in his Sunday "best,” a white shirt minus the tie, and suit, perhaps his only suit, smoking a Pall Mall and finishing a cup of tea. After breakfast, the five of us stepped off into the brilliant sunshine, Lynn and I holding my mom’s hand and my dad carrying Maggie on his shoulders as we headed for the subway. We descended into the cool, dark entrance and heard the screeching of braking subway cars and the roar of accelerating cars disappearing into the darkness and hurtling to their next stop. The noise and organized chaos of subway life, people rushing to and from their destinations, excited me and still does. We waited impatiently for the next train and boarded it with the other riders; many dressed like my parents in their Sunday best. Laughter and an air of excitement filled the car with a festive mood. As the train moved down the line, more people joined, adding to the merriment. At one stop, the doors opened, and everyone on the train exited at once in a loud crowd. The vibrantly colored column snaked towards the stairs, headed for the exits with our family sandwiched amongst the masses, and entered the fresh air and blinding sunshine.

We followed the multitude of people, which picked up the pace and became more excited and louder. The air changed to a different smell, and the landscape opened, more open than Lynch St. Suddenly, the skyline was filled with enormous skeleton-like structures and the sound of laughter and screams. The sound and new smells of the sea and foods, rattling roller coasters, and other machines left me speechless and mesmerized, this was Coney Island. We walked through the crowds onto a soft surface that filled my shoes and gave way when I stepped on it. Sand! My mom said this was the beach, and we would have fun, but my tiny mind was dubious. Ten minutes of face-planting, spitting sand from my mouth, and feeling itchy because the sand had worked its way into every orifice on my body convinced me I was right.

I started to protest; whining is a more accurate description, to be honest. One look at my dad's face told me I had lit his fuse. A stern warning and a clip on the back of my head convinced me my silence might be a better option. Our first day at the beach ended with three cranky, sunburned, itchy kids ready for our bath and bed, my mom ready for the day to end, and my dad thirsty. At the junction of Marcy Avenue and Lynch Street, he kissed us on the head goodnight and headed towards the bar, the allure of the bottle stronger than family time. His spiral continued.

July 17th, 1961, was another regular day in my six-year-old life. My mom and us kids were in the kitchen when my dad walked in from work unexpectedly. He sat down at the table, his head buried in his hands, shaking his head as he talked to her. She rubbed his back in a soothing gesture and talked gently back. My mom made him a sandwich, but he rose from the table without eating it and went into the bedroom for a nap. The haunted image of that single sandwich on a white plate, uneaten, has never left my memory. Later that afternoon, my mom cooked supper, and as we were getting ready to sit down, she sent Lynn into the bedroom to wake my dad. After a minute or two, Lynn appeared at the bedroom door, looking tiny with her page boy bangs. In a barely audible whisper said, “Mommy, Daddy won't wake up."

"Jimmy, your suppers on the table," my mom called out. No answer. She got up from the table and made her way into the bedroom. A banshee-like shriek pierced the apartment as my mother stumbled from the bedroom, wide-eyed in hysterics. She rushed by us and made it out to the hallway, shrieking. I heard chairs scraping across the floors and people running from Rosario's apartment, no doubt alarmed by my mom's screaming. I entered the bedroom and saw my dad lying on the bed, curled up and looking fast asleep. Lynn crawled on top of him and repeated, "Daddy, Daddy," as she pressed against his face. I crawled onto the bed, joined in on this new game, and climbed over him, thinking he was playing with us.

Mr. Rosario burst into the bedroom, picked us off my dad, and gently passed us to someone, another man, a stranger to me. He carried me through the kitchen and sat me on the couch beside Maggie in the living room; Lynn joined us a minute later. I saw Mrs. Rosario with her arms wrapped around my mom, doing her best to comfort her as she sobbed, occasionally letting out a frightening scream, "No, Jimmy, no! The wail of sirens, flashing lights, and the crackle of radio transmissions swamped the street, and soon, the apartment overflowed with strangers. Police officers, firefighters, men with notebooks asking questions, and people in white coats crammed into the apartment. Fear, confusion, and bewilderment added to this traumatizing scene and frightened me. Some members of the Rosario clan arrived and removed us from the chaos and commotion upstairs to their apartment. The dark, unlit hallway, reverberating with laughter and joy only days ago, was replaced by sirens and men in uniform.

My father died in Brooklyn, an alcoholic, at age thirty-one. The remaining weeks and months are a blur as my mother prepared us for her return to the city and land of her birth, Belfast, Northern Ireland, and my future home for the next seventeen years. The concrete jungle of Brooklyn and New York soon gave way to Connecticut's wide-open countryside and fresh air. We stayed with my aunt until our passports and all the necessary paperwork was completed, My mom's promise of a fresh beginning in a new land (at least for us kids) with her parents and the rest of our extended family sounded warm, exciting, and safe. She was wrong, so very wrong. We went from the frying pan into the fire, the abuse had only just begun.

No comments:

Post a Comment